Have you ever wondered why you snap at the people you love most? Why your mind goes completely blank in important meetings? Or why some days you feel unstoppable, while others you can barely drag yourself out of bed?

The answer isn’t willpower. It isn’t a character flaw. And it certainly isn’t something wrong with you.

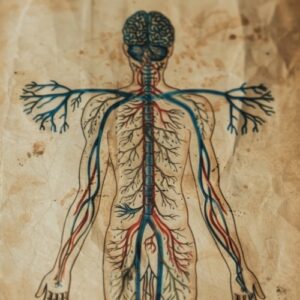

The answer lies in your nervous system — specifically, in understanding the different states it moves through throughout each day, often without your conscious awareness.

This understanding has transformed how therapists, healers, and individuals approach everything from anxiety and depression to relationship difficulties and chronic fatigue. And once you grasp these concepts, you’ll never look at your reactions — or anyone else’s — the same way again.

What is the Autonomic Nervous System?

Before diving into the states themselves, it helps to understand what we’re actually talking about when we discuss the nervous system in this context.

Your autonomic nervous system (ANS) is the part of your nervous system that operates largely outside your conscious control. It regulates your heart rate, digestion, respiratory rate, pupil response, and — crucially — your stress responses. It’s constantly scanning your environment for cues of safety or danger and adjusting your physiology accordingly.

For decades, scientists believed the ANS operated as a simple two-part system: the sympathetic branch (fight or flight) and the parasympathetic branch (rest and digest). Stressed? Sympathetic kicks in. Safe? Parasympathetic takes over.

But this model couldn’t explain certain phenomena. Why do some people freeze rather than fight or flee? Why do trauma survivors sometimes shut down completely, becoming numb and disconnected? Why can someone feel simultaneously wired and exhausted?

Enter polyvagal theory.

Polyvagal Theory: A New Map of the Nervous System

Developed by neuroscientist Dr. Stephen Porges in the 1990s, polyvagal theory provides a more nuanced understanding of how our nervous system responds to the world. The name comes from the vagus nerve — the longest cranial nerve in the body, running from the brainstem all the way down to the abdomen.

Porges discovered that the vagus nerve actually has two distinct branches, each with different evolutionary origins and different functions. This insight led to a model that identifies not two, but three primary neural circuits — and four distinct states that humans move through.

Understanding these states isn’t just academic. It’s profoundly practical. Because once you can recognise which state you’re in, you gain the ability to consciously support your system in returning to balance.

The Four Nervous System States Explained

1. Ventral Vagal State: Safety and Social Connection

The ventral vagal state is your optimal functioning zone. When you’re here, you feel safe, connected, and present. Your heart rate is steady, your breathing is relaxed, and your facial muscles are soft and expressive. You can think clearly, engage with others, and respond flexibly to whatever arises.

This state is mediated by the ventral branch of the vagus nerve — the evolutionarily newer portion that’s unique to mammals. It’s sometimes called the “social engagement system” because it enables the nuanced facial expressions, vocal tones, and attentive listening that make genuine connection possible.

Signs you’re in ventral vagal state include feeling grounded and present, being able to make eye contact comfortably, breathing easily, feeling curious rather than defensive, and being able to access both your thoughts and feelings.

2. Sympathetic State: Mobilisation and Fight-or-Flight

When your nervous system detects a threat, it shifts into sympathetic activation. This is the well-known fight-or-flight response, and it’s designed to mobilise your body for action.

Your heart rate increases, breathing becomes rapid and shallow, stress hormones flood your bloodstream, and blood flow is redirected away from digestion and toward your muscles. Your pupils dilate to take in more visual information. Your hearing sharpens. You’re primed to either confront the danger or escape it.

This response evolved to help our ancestors survive genuine physical threats — predators, natural disasters, hostile encounters. The problem is that our modern nervous systems can’t always distinguish between a charging lion and a critical email from our boss. Both can trigger the same cascade of physiological changes.

Signs of sympathetic activation include racing heart, shallow breathing, feeling restless or unable to sit still, irritability or anger, anxiety or panic, difficulty concentrating, and an urgent sense that you need to DO something.

3. Freeze State: Immobilisation with Fear

The freeze response occurs when your system perceives a threat but determines that neither fighting nor fleeing is possible. It’s like having one foot on the accelerator (sympathetic activation) and one foot on the brake (dorsal vagal) simultaneously.

In this state, there’s high physiological arousal combined with an inability to move or act. You might feel stuck, rigid, or paralysed. Your mind might go blank. You might hold your breath without realising it.

Many people experience freeze during overwhelming situations — the moment when someone says something hurtful and you can’t think of a response, or when you’re so overwhelmed by your to-do list that you just stare at it, unable to start anything.

The freeze response is actually adaptive in certain situations. Playing dead can be a survival strategy when a predator has already caught you. But in modern life, getting stuck in freeze can be deeply frustrating and confusing.

4. Dorsal Vagal State: Shutdown and Disconnection

The dorsal vagal state represents the oldest part of our autonomic nervous system — one we share with reptiles. It’s the ultimate conservation mode, activated when the nervous system determines that the threat is inescapable and fighting or fleeing would be futile.

In dorsal vagal shutdown, everything slows down. Heart rate drops, breathing becomes shallow, blood pressure decreases. You might feel numb, disconnected, hopeless, or exhausted. Some people describe it as feeling like they’re watching their life through a window, or like they’re wrapped in cotton wool.

This state served our ancestors well in certain extreme situations — the numbness that accompanies it can reduce pain and fear during inescapable danger. But when we get stuck here in response to chronic stress rather than acute physical threat, it can manifest as depression, dissociation, chronic fatigue, or a pervasive sense of hopelessness.

Signs of dorsal vagal shutdown include feeling numb or disconnected, difficulty feeling emotions, fatigue that sleep doesn’t resolve, a sense of hopelessness or meaninglessness, withdrawing from social contact, and difficulty completing tasks or making decisions.

Why Understanding Your Nervous System States Changes Everything

Here’s why this knowledge is so transformative: when you can recognise which state you’re in, you shift from being lost in the experience to being an observer of it.

Instead of thinking “I’m so anxious — what’s wrong with me?” you can recognise “My nervous system has shifted into sympathetic activation. It’s trying to protect me from something it perceives as a threat.”

Instead of “I’m so lazy and useless — why can’t I just get things done?” you can understand “I’ve dropped into dorsal vagal. My system has gone into conservation mode because it’s overwhelmed.”

This shift from self-judgment to self-understanding is profound. It creates space for compassion rather than criticism. And from that place of compassion, genuine regulation becomes possible.

The Path to Regulation: Working With Your Nervous System

One of the most important insights from polyvagal theory is that we can’t simply think our way out of nervous system dysregulation. You’ve probably noticed this yourself — telling yourself to “just calm down” when you’re anxious rarely works. That’s because these states are physiological, not cognitive.

This is where somatic approaches become so valuable. By working with the body — through breath, movement, sound, and sensation — we can communicate with the nervous system in its own language.

Some practices that can help shift your state include slow, extended exhales to activate the parasympathetic nervous system, gentle movement or shaking to release trapped activation, humming or singing to stimulate the vagus nerve, orienting to your environment to signal safety to your system, and co-regulation with another calm, regulated person.

The goal isn’t to never leave the ventral vagal state — that’s neither possible nor desirable. Appropriate sympathetic activation helps us meet challenges and take action. Even dorsal vagal has its place in allowing deep rest and recovery.

The goal is flexibility: the ability to move through states fluidly in response to what’s actually happening, rather than getting stuck in chronic activation or shutdown.

Guided Practice: Mapping Your Nervous System States

The best way to understand these concepts isn’t just to read about them — it’s to experience them in your own body. I’ve created a guided meditation that will help you recognise how each nervous system state feels specifically for you.

In this practice, we’ll journey through each state gently and safely, building your capacity to recognise your nervous system’s signals. This body awareness is the foundation of all self-regulation work.

Moving Forward: From Understanding to Embodiment

Understanding polyvagal theory intellectually is just the beginning. The real transformation comes from learning to recognise these states in your daily life and developing practices that support your system in returning to regulation.

This isn’t about perfection. It’s not about never getting triggered or always feeling calm. It’s about developing a relationship with your nervous system — learning its language, understanding its protective intentions, and working with it rather than against it.

Every time you pause to notice what state you’re in, you’re building neural pathways that support self-awareness. Every time you offer yourself compassion instead of criticism, you’re signalling safety to your system. Every time you consciously support your body in returning to regulation, you’re strengthening your capacity for resilience.

Your nervous system has been working hard to protect you your entire life. Now it’s time to work together.